From mono to stereo: IBS’s proposal at the Integration Conference

Every November brings an important gathering for everyone who works on making sense of integration in Estonia. At this year’s Integration Conference, Kristjan Kaldur, Head of Migration and Integration Research Programme at the Institute of Baltic Studies, spoke about what it means to have a sense of belonging without a passport, and how the way we name groups of people shapes who we “see” in society at all. His presentation drew on a recent study on the attitudes, identities and barriers to acquiring citizenship among people with undefined citizenship living in Estonia – i.e. the stateless people.

The study shows that people with undefined citizenship are not a homogeneous grey mass, but fall into several identity groups – from those who feel a strong sense of belonging to Estonia, to those whose identity is more borderline or fragmented.

“Russian-speaking Estonian” does not fit into Excel, but lives in real life

We saw that if we offer people with undefined citizenship only the classic monoethnic group labels – such as Estonian, Russian, Ukrainian, Belarusian and so on – we receive in return the same black-and-white, and in many ways colour-blind, categories. But when we give respondents the option to choose, alongside these, other more flexible categories, we see a remarkable shift: three quarters of respondents abandon their monoethnic category and instead choose a hybrid group label, such as “Russian-speaking Estonian” (38%) or “Estonian Russian” (19%).

The results therefore show that a significant share of people with undefined citizenship have adopted an “Estonian” marker or attribute and feel that Estonia is also their homeland. The results also indicate that they express their passive loyalty to the Estonian state precisely by not taking up another country’s citizenship. At the same time, however, they feel rejected, disappointed and drained of hope.

Kristjan emphasised that the decision to apply for citizenship therefore does not depend only on language skills or the ability to pass an exam, but also on whether a person feels genuinely wanted and treated fairly in Estonia. The question posed to the Estonian state and its institutions at the conference was therefore twofold: how to lower practical barriers (information, exams, bureaucracy) and, at the same time, how to use categories and language that do not push people’s identities to the margins, but instead help them feel part of Estonia’s “we”.

Estonia’s “we” is broader than our integration policy dares to admit

In other words: the way we measure identities produces the identities we end up seeing. If we design policies solely on the basis of monoethnic categories, we are in fact reading the room wrong. And by misreading it, we amplify narratives that are not true.

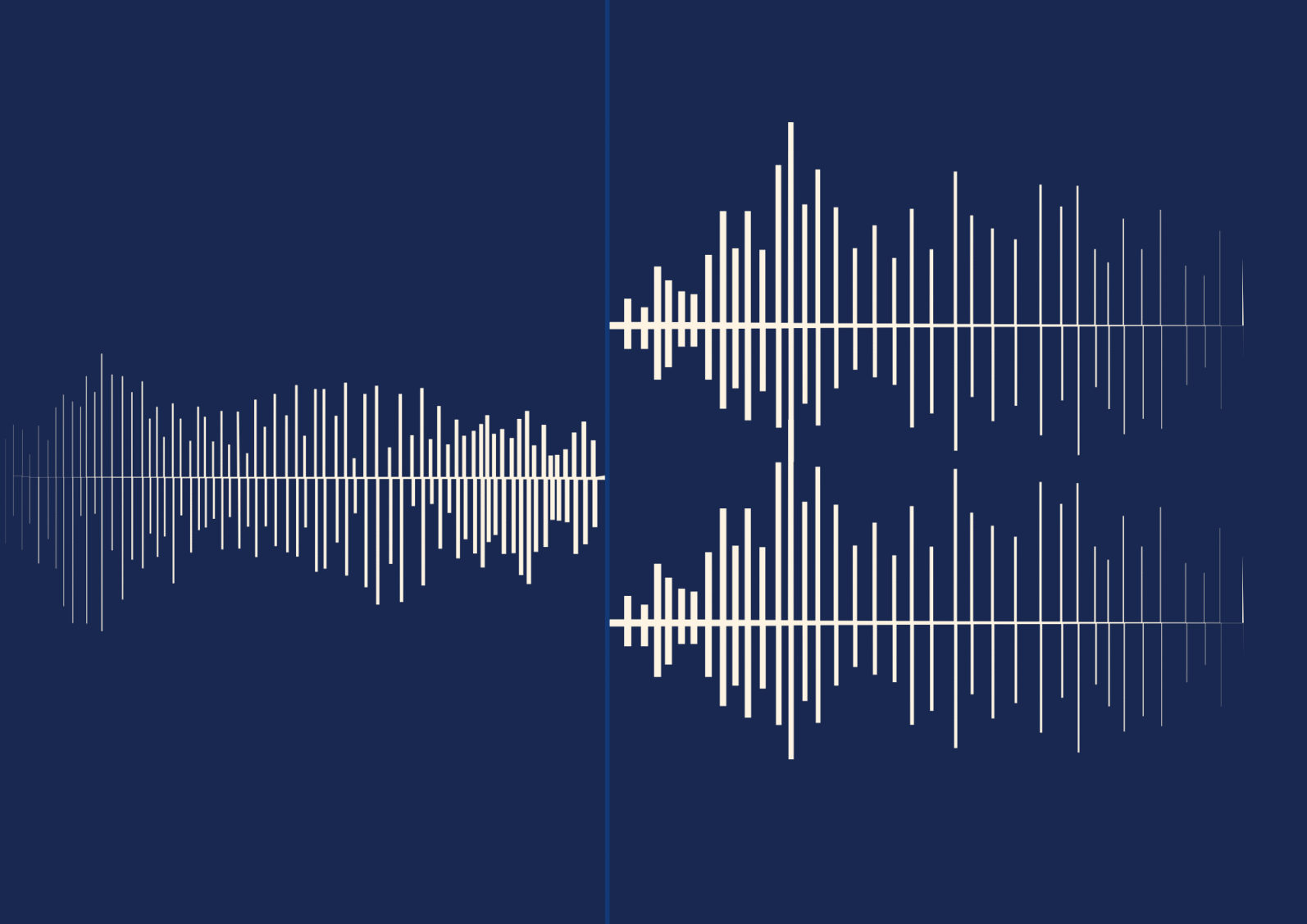

So if, as a state, we were able to see beyond mono-identities (Estonian, Russian, Ukrainian and so on) and recognise the hybrid identities behind them, it would be as revolutionary as the shift in the world of sound from mono to stereo.

You can read more in the study report that formed the basis for the conference presentation here (in Estonian): https://www.ibs.ee/wp-content/uploads/Maaratlemata-kodakondsusega-isikud-uuringuaruanne.pdf